Concurrency does not imply complexity

When complexity makes the RTOS brittle

In embedded systems, complexity is often treated as a signal that an RTOS is required.

As applications grow, responsibilities multiply, execution paths diversify, and scheduling becomes explicit. At small scale, this intuition holds. At larger scale, it begins to fail in a less obvious way.

The failure is not functional. It is architectural.

The steady-state illusion

In steady state, systems benefit from properties that are rarely modeled explicitly.

Execution paths are predictable. Rare branches remain dormant. Memory pressure stays within margins that feel comfortable. As long as nothing changes, assumptions hold.

An RTOS fits naturally into this environment. Tasks are defined, stacks are sized conservatively, and the scheduler keeps concerns separated. The system behaves correctly.

The illusion is that this structure will continue to hold as the system grows.

Where growth changes the rules

Growth in embedded systems rarely comes from rewriting core logic. It comes from adding surface area.

Storage appears. Diagnostics appear. Interfaces for human interaction appear. None of these change the fundamental behavior of the system, but they change how that behavior is exercised.

At that point, complexity stops being logical and starts being structural.

A concrete failure mode

In one design, the core application logic was not particularly complex. The system performed periodic sensing, interacted with a cellular modem, and retried transmissions when required.

An RTOS was used to structure this work. Each concern was isolated into its own task. Under initial conditions, the system behaved correctly.

The failure appeared later, not when behavior changed, but when surface area did.

Adding a NAND driver introduced deeper call paths and temporary buffers. Adding a CLI introduced irregular execution patterns and stack usage that depended on command depth rather than steady-state behavior.

Individually, neither addition was problematic. Together, they pushed the memory model past its margins.

Each task carried its own stack, sized conservatively to survive worst-case paths. That sizing was not precise. It could not be.

Stack usage depends on call depth, error handling, library behavior, and rarely executed branches. The values were estimates, chosen to be safe rather than exact.

As new components were added, those estimates accumulated.

The system did not fail immediately. It failed only when rarely exercised paths aligned: storage operations invoking deep call chains, CLI interaction expanding stack usage, and modem retries occurring within the same execution window.

At that point, stack overflow corrupted adjacent memory and the system reset or faulted.

Nothing about the logic was incorrect. The estimates had simply stopped holding.

Why this failure appears late

The key is not that memory was insufficient, but that memory was committed speculatively.

An RTOS requires stack space to be allocated per task based on anticipated worst-case execution. That anticipation becomes less accurate as surface area grows. Each new feature adds call depth and variability, but the original estimates remain frozen in place.

Steady state hides this risk. Rare paths do not execute often enough to collide. Growth increases the number of ways those paths can overlap.

By the time the failure appears, the system has already shipped. The abstraction worked until the uncertainty it carried became operational.

Memory commitment is the point

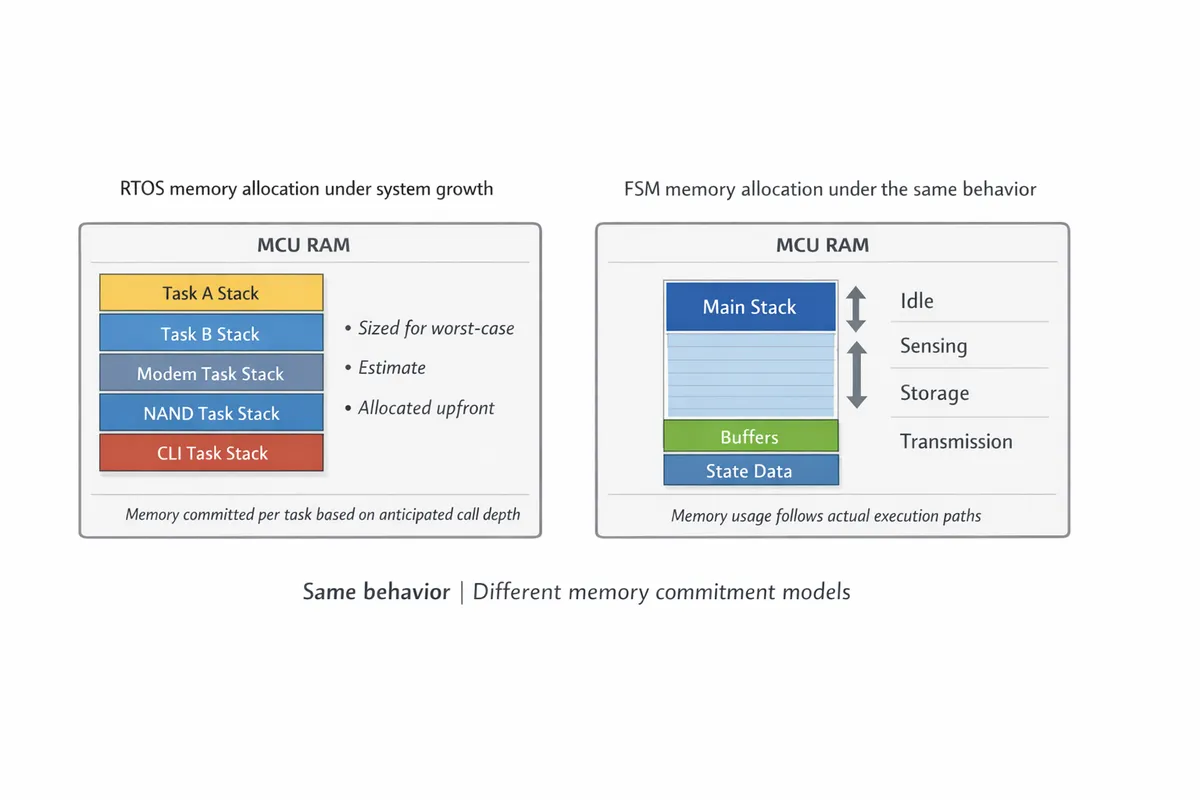

This is easier to see when you look at how memory is committed under each model.

RTOS task stacks commit memory early based on estimated worst-case call depth. A single-stack FSM model keeps cost centralized and makes growth easier to reason about.

What changes with an explicit state machine

When the same behavior was expressed as an explicit finite state machine running on a single stack, the failure mode disappeared.

Not because the system became simpler, but because memory stopped being fragmented across speculative execution contexts. Call depth became visible. Resource usage became bounded. Growth no longer multiplied hidden commitments.

The work was the same. The model was not.

Execution paths were explicit. Transitions were deliberate. Memory usage reflected actual behavior rather than anticipated concurrency.

Complexity versus commitment

This is where many discussions go wrong.

Complexity of behavior does not automatically imply complexity of execution. A system can have many states without needing many stacks. It can perform many roles without performing them concurrently.

RTOS-based designs excel when true concurrency is required. They become fragile when concurrency is assumed as a proxy for growth.

FSM-based designs do not eliminate complexity. They make its cost explicit.

What this says about RTOS usage

This is not an argument against RTOS-based design.

RTOSes are powerful tools. They enable true concurrency, isolation of concerns, and structured scheduling. Many systems require them and benefit from them.

The risk is not in using an RTOS. It is in assuming that its cost model remains transparent as systems grow on constrained hardware.

Task stacks are allocated based on estimates. Those estimates must account for future paths that may not yet exist. As surface area increases, uncertainty increases with it.

If that uncertainty is not revisited explicitly, failures appear late and without a clear cause.

Where this leaves design decisions

Choosing between an RTOS and an explicit state machine is not a matter of simplicity versus sophistication.

It is a matter of when and how resource commitments are made.

FSM-based designs defer those commitments until execution paths are explicit. RTOS-based designs commit early in exchange for concurrency.

Both are valid. Both have costs.

The important distinction is whether those costs remain visible as the system evolves.

Steady state makes many assumptions appear safe. Growth is what tests them.