If it can break you, it's part of your system

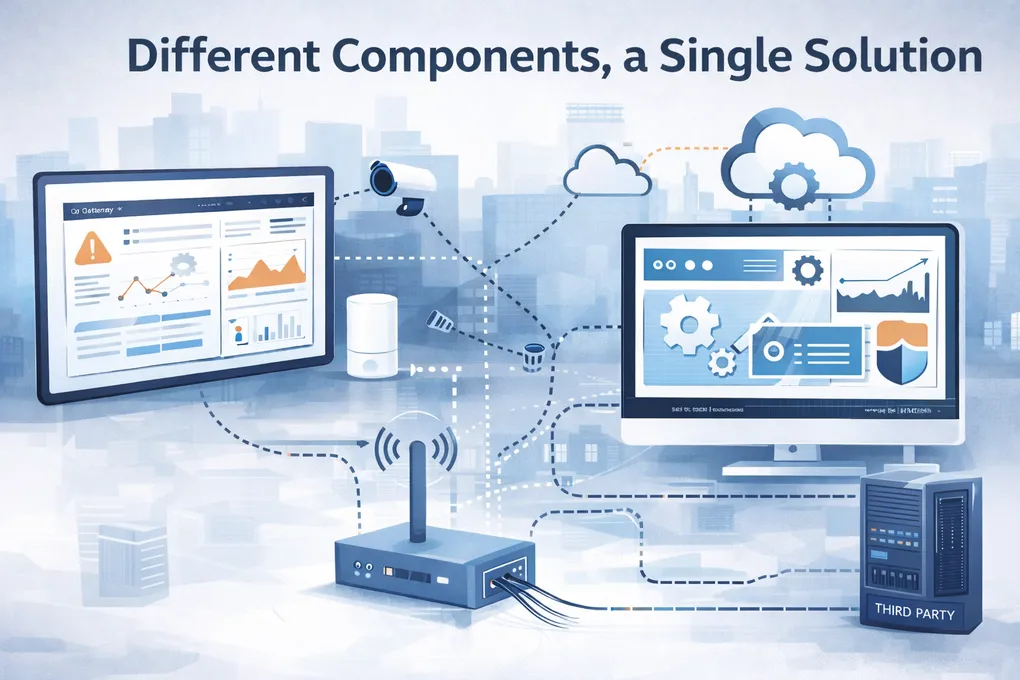

Different components, a single solution

Recently I was on a support call with a customer. They deploy a large number of devices and use our IoT platform for ingestion, management, dashboarding, and reporting. The devices themselves are also ours.

On the surface, this should have been a straightforward support issue. We own the devices. We own the ingestion layer. We own the analytics. And yet, a subset of devices had silently stopped delivering usable data.

Initial checks didn’t show anything obviously wrong. Other devices were reporting correctly. No application logic had changed. Nothing looked broken in the places we usually look first.

After digging deeper, we found the culprit: a callback configuration on the network server the devices were using. More specifically, a configuration on a third-party network server that we don’t control directly.

At that point, a tempting conclusion appears: there’s nothing wrong with our system.

And technically, that’s true.

From the customer’s perspective, it isn’t.

Everything involved in getting data from device to dashboard is part of the solution, whether we own it or not.

What you don’t own still has impact on your system

This sounds obvious, but it’s often misunderstood.

In this case, the callback configuration was syntactically correct. No invalid fields. No malformed JSON. The issue was subtle: a header value was wrong. That single detail caused the payload to be rejected by our ingestion layer as malformed.

The result was a client-side error and a rejected message. This is correct behavior. A malformed payload should not result in a server error.

And yet, the system was broken.

This is where things get uncomfortable. Because the failure surfaced as a client error, most alerting systems wouldn’t flag it. No 5xx spike. No crash. No retry storm. Just devices quietly failing to ingest data.

Where do you draw the line between “expected client errors” and “a critical component of the system not functioning”?

In practice, many IoT systems draw that line too rigidly, and miss exactly these kinds of failures.

The problematic mindset

At the heart of the problem is a mindset that works well in simpler systems: responsibility ends at the components you directly own.

That assumption breaks down quickly in IoT.

Very few IoT solutions are vertically integrated end-to-end. Devices, networks, gateways, ingestion pipelines, and applications are usually built and operated by different teams, sometimes different companies entirely. Interoperability is not optional; it’s foundational.

But this interoperability is not the same as calling a third-party REST API to send an email and forgetting about it. In many IoT deployments, communication is continuous, bidirectional, and stateful. Networks are not just transport, they behave like active system components.

When a misconfiguration or schema mismatch appears anywhere along that chain, the entire solution is affected. From an architectural or development standpoint, it may be easy to say “that’s not our component.”

From the end user’s point of view, that distinction doesn’t exist.

Indirect ownership is still ownership

Ignoring indirect ownership doesn’t just increase operational risk, it actively makes systems brittle.

At best, failures remain silent until customers report them.

At worst, systems fail suddenly in ways that are difficult to diagnose or attribute.

The idea that responsibility stops at clearly defined boundaries only works in isolation. Real IoT systems don’t operate in isolation. They are supply chains of components, and weak links are rarely owned by a single team.

Treating third-party systems as invisible boundary agents guarantees fragility. Treating them as first-class components, even if you don’t own them, at least gives you a chance to detect, reason about, and respond to failures.

What this implies for system design

This doesn’t mean you can or should absorb responsibility for everything.

It does mean acknowledging that some failures cannot be handled with retries, timeouts, or generic alerting rules. A blanket policy that ignores client errors will miss real outages. A policy that alerts on every one will drown teams in noise.

The only viable approach is more explicit modeling:

- Different classes of client errors need different handling depending on which component produced them.

- Alerting should reflect operational impact, not just protocol semantics.

- Defensive ingestion should assume upstream systems will misbehave, even when they are “working as designed”.

This applies symmetrically across the system. While I’m describing this from the perspective of an ingestion platform, the same logic applies to network servers, device firmware, and downstream applications.

APIs matter more than dashboards

One thing that consistently makes indirect ownership easier to manage is programmatic access across the stack.

Many platforms advertise APIs, but in practice those APIs often expose data, not control. You can query device state, metrics, or historical records, but not the configuration that determines how data flows in the first place.

Callback configuration, routing rules, transformation logic, and integration settings are often only available through GUIs. When those elements break, diagnosis becomes manual and slow.

Exposing configuration and control surfaces via APIs doesn’t eliminate failures, but it makes them observable, automatable, and, in some cases, self-healing.

Without that, operational reliability depends on humans noticing subtle mismatches before customers do.

Where this leads

It’s easy to dismiss incidents like this as isolated misconfigurations. The fix is quick. The system recovers. Everyone moves on.

But the pattern is familiar: a customer reports a failure, a team discovers an external misconfiguration, it gets corrected, and nothing changes structurally.

As long as teams treat indirect dependencies as “outside the system”, these failures will repeat. Not because anyone is careless, but because the system itself is blind to part of its own operation.

IoT solutions don’t usually fail because a single component is wrong. They fail because responsibility is fragmented while expectations are unified.

If a component can break your system, it is part of your system, whether you own it or not.