When responsibility boundaries disappear in embedded systems

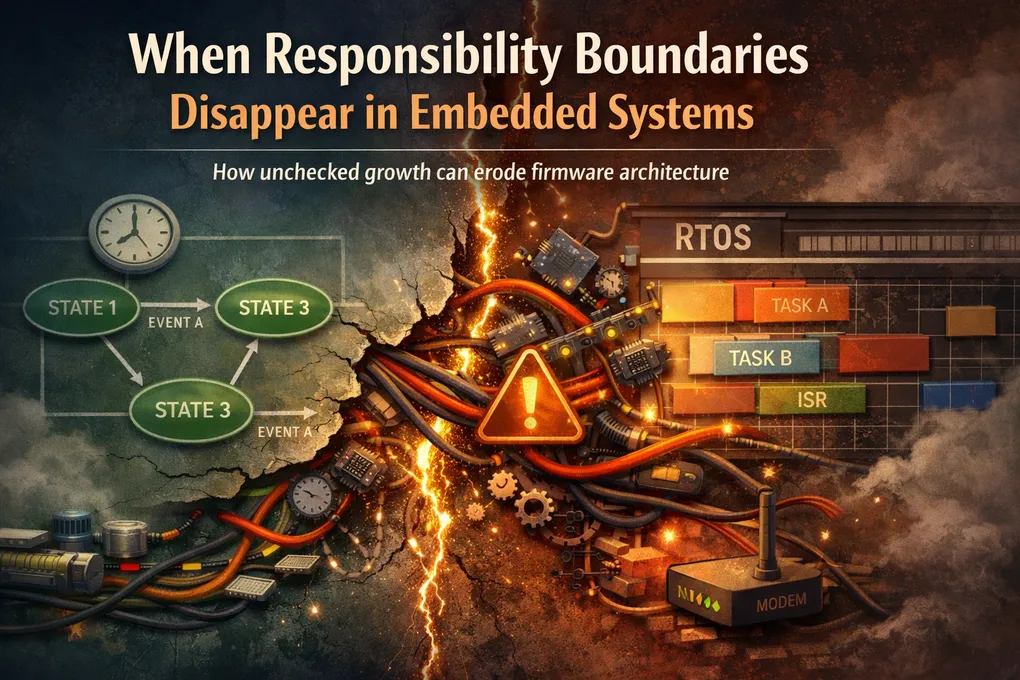

As embedded code grows, the likelihood of responsibilities creeping into components that were never meant to own them increases. This growth is a natural part of software evolution, but without clear and explicit contracts, systems slowly lose the ability to be reasoned about in terms of timing, ownership, and failure modes.

This can take many shapes. A driver might start assuming business logic and depending on global state, or a higher-level component might reach directly into hardware and dictate timing.

When each component becomes a mini program in and of itself, the probability of unpredictable behavior and issues in the field increases significantly.

When design becomes an afterthought

The root cause of most of these issues is rarely a lack of technical competence. More often, it is pressure to deliver new features or accommodate new requirements quickly.

Under those conditions, design decisions tend to be local, and the global structure of the system is temporarily ignored. The focus shifts to making a specific component work. Over time, these local decisions accumulate into technical debt that is difficult to unwind.

What makes this class of problems particularly insidious is that they compound. An implementation shortcut taken today becomes an assumption for the next iteration. Code is built around it. Timing expectations shift. Responsibilities blur. Eventually, recognizable patterns disappear, and reasoning about known states or execution timing becomes increasingly difficult.

This pattern can appear in many forms. One particularly illustrative case is a device that evolved over time to support multiple communication technologies.

To highlight this point, consider a device that collects data from simple sources, such as pulse counting. Initially the device uses a single type of modem, such as LoRaWAN or cellular. But over time requirements dictate that additional versions of the device exist, each with different communications technologies.

Each device can drive a single modem, but to solve this the engineering team reasons that it’s better to maintain a single code base that has the capability of detecting and running the correct type of modem automatically.

This is a reasonable, and sensible, consideration. The problem comes when deadlines are close and the product is developed just to solve this particular requirement. A particular problematic pattern could be the following code snippet, simplified for the sake of this example.

while (true) {

normal_operation_while_lora_is_busy(&windowStart);

if (serial_available()) {

read_byte_into_buffer();

if (strstr(rx, "OK")) break;

}

if (timed_out()) break;

}At a glance, this looks like a reasonable compromise between responsiveness and simplicity. In this case the reasoning is to allow for the commands to work within the timing constraints of the modem (in our example a LoRaWAN modem). This means send a command (most likely an AT command), and then just wait for the reply. The assumption, however, is that the device must continue performing other work: sensor readings, battery management, or whatever else is required.

Given the time constraints, one solution is to reintroduce the main loop into this blocking structure, which is exactly what normal_operation_while_lora_is_busy does.

void normal_operation_while_lora_is_busy(uint32_t *windowStart) {

if (HAL_GetTick() - *windowStart >= ONE_SECOND_MS) {

schedule_check();

cli_manager();

modbus_handle_sampling();

*windowStart = HAL_GetTick();

}

}which is effectively re-implementing part of the main loop inside a driver.

This leads to several critical consequences. For starters, there’s code duplication and high coupling with other logic, which is dangerous when the code is constantly changing, as a change in the main loop might not be reflected here, which in the end might create two different types of logic for the same kind of operation.

The driver is now making timing decisions that extend beyond its scope, which makes it significantly harder to reason about system-level timing.

This creates code that’s extremely brittle, and that will more likely than not fail in unexpected ways when deployed. What’s worse, it might not be caught in development due to its unpredictability.

This type of code is not necessarily a reflection on an incompetent or not technically strong team, but rather a consequence of organic growth in code that has to respond quickly to new demands. The two snippets above showcase what happens when the design, or the implementation to be more accurate, don’t explicitly define what the responsibilities for each layer are, and then ensure the enforcement of this criteria is done strictly.

Designing for ownership

It’s an almost obvious thing to define, but at all points in the design of firmware architecture (can apply to all software actually), the main idea is to ask, who owns what; or maybe better put, what responsibilities each component owns.

This single question allows the architecture to keep growing without the responsibilities of a feature to creep into places that shouldn’t own it. Keeping with the example we’ve shown, we’ll highlight how the responsibility-first design approach would treat this same modem structure in a way that can maintain a clear decoupling of all the different actions the device needs to take.

The first consideration is that independent of the communication technology being used, the driver itself needs to handle a single contract: pass on the serial commands to the modem, poll and retrieve the response in a non-blocking way.

This simple definition exposes one critical observation: the underlying mechanism is the same independent of the network. The actual parameters will differ, but the mechanism remains the same.

If taken to implementation, this approach does two things: First it removes a lot of pressure on memory, as redundant buffers and variables are collapsed into unique symbols that live in a single place. But also, it treats the specific network components as wrappers to a unified driver, with variations in the parameters, and timings each network expects, while not touching the actual mechanics of talking to the modem.

This pattern becomes viable in a non-blocking design once two constraints are enforced:

- The transmission and reception are two separate steps, that shouldn’t be unified in a function, this in particular is a quick way to start generating blocking code.

- We can just poll the data, but we don’t need to get stuck in a loop waiting for it, we can leverage interrupts and a simple polling function that reads the internal RX buffer.

These two observations lead to a complete decoupling of the modem operation and allow the code to resurface to the main loop (or FSM or whatever is being used) and don’t get stuck inside individual components for long periods, in the order of seconds.

The expression of these observations leads to two important considerations in the code. First, the parameters are network specific, but they should appear in a uniform way, so even though the driver doesn’t know what specific command or terminations we’re expecting, or what a success or error looks like, we can still consume those elements and act on them in a generalized way. In the example we can see this as a simple structure as the following.

typedef struct {

const char* success_patterns[MAX_PATTERNS];

const char* error_patterns[MAX_PATTERNS];

uint32_t timeout_ms;

} modem_cmd_params_t;Where the elements that are specific to each modem, or command, are defined as variables we can use. This decouples specific operations and allows the driver to still work on different technologies with no updates to the logic.

The second thing, as we discussed, is the total separation of what is a transmission and what is a reception. Splitting the two operations and treating them as totally independent steps makes it possible for the main loop to just send a command and then periodically poll, but is not trapped in a single blocking operation until that operation is done.

So the transmission is treated in this way. The example is a simplified version for the sake of the explanation.

bool modem_send(const char *cmd, modem_cmd_params_t *params) {

write_uart(cmd);

ctx.busy = true;

ctx.start = tick_now();

ctx.timeout = params->timeout_ms;

copy_patterns(ctx.success, params->success_patterns);

copy_patterns(ctx.error, params->error_patterns);

return true;

}While the reception is an actual polling that just tells the main loop if the response is complete or not. Below is a possible way of implementing this, simplified as the other blocks.

bool modem_poll(void) {

drain_uart_into_response_buffer();

if (match_any(ctx.response, ctx.success)) complete_success();

if (match_any(ctx.response, ctx.error)) complete_error();

if (elapsed() >= ctx.timeout) complete_timeout();

return ctx.completed;

}Here, the two ideas that are predominant are, that each call to poll just returns what the status of the specific operation is, it doesn’t linger waiting for the operation to complete, but also returns the actual status so the application code (main loop), decides what to do next.

Additionally, this poll function does two things: It reads whatever is on the serial buffer and places it into its own, but also parses the response with regards to the parameters passed, that way we can know if what we’re seeing is a timeout, a success or an error.

This pattern works, because responsibility is clearly designed from the start, and any future functionality can be added as additional parameters or application code, but within their own boundaries. What talks to the modem remains as a single block with a single responsibility.

Is this approach generalizable?

One last concern that might arise from this explanation is that, the approach works fine on “simpler” architectures: a loop, an FSM; things that don’t really need concurrency. But what happens when we throw an RTOS into the mix? Does this assumption break?

The answer is that not quite. The inclusion of an RTOS shouldn’t exclude the need for clear boundaries in the design and implementation of the components, we just switch what happens from the main loop, to the specific task. As in the end, any design involving a communications module will probably require a specific task to handle this type of things.

The takeaway from this type of refactor is not that a particular pattern or abstraction is superior. It is that systems without clear ownership boundaries tend to grow in unpredictable ways.

When responsibilities are not explicitly defined and enforced, code begins to compensate implicitly. Timing assumptions leak. Components take on work they were never designed to own. Failures surface in the field, where access is limited and fixes are costly.

Clear contracts do not eliminate complexity, but they localize it. They make growth intentional rather than accidental, and they keep systems understandable long after the original design assumptions have stopped holding.